about the artist - Miria Miria

Miria Miria is a cross-media artist whose practice spans painting, assemblage, installation, costume, and performance, creating constellations of interconnected works. Originally from Japan, she has lived and worked across Asia, Oceania, and the UK. Her artistic journey began in her 50s, bringing a distinct perspective shaped by diverse cultural and political environments. She holds a First Class Honours BA in Fine Art from Goldsmiths, University of London, and an MFA with Distinction from BALTIC x Northumbria University. Her work has been exhibited in the UK and internationally, including solo exhibitions in Melbourne and Redcar. She currently works from her studio at Redcar Contemporary Art Gallery, where she continues to explore the layered relationships between human and non-human worlds.

future tense - Becoming

Using found plastics as the main material, Miria creates numerous assemblages that feel at once artificial and organic. These works form immersive installations—constellations of altered ecologies—where viewers navigate between stillness and transformation. Costumes mirroring the assemblages are worn by performers or displayed on mannequins, blurring the line between object and body. Each material is treated as a collaborator, with forms emerging intuitively, constructed through balance rather than glue. The work rethinks how we coexist with what we’ve forgotten or overlooked, offering moments of playful, poetic reflection within imagined, surreal ecosystems.

The artist surrounded by numerous assemblages created with unwanted plastics using only balance, engaging in an almost collaborative process with the discarded materials. The resulting figurative forms quietly question our environmental impact and our relationship with the materials.

Photo above left

Photo above right

Costumed performers mirror the assemblage behind them, dissolving the line between human bodies and non-human forms.

Photos below

future tense - Becoming installation view. Assemblages are placed on natural wooden plinths of varying heights, evoking a landscape of trees and open fields.

Assemblages created using unwanted plastics and clay only used balance resembling human figures. Costumed performers mirror the assemblage dissolving the line between human bodies and non-human forms.

Photos above

The performance Becoming – The performer immerses in the assemblage, expressing the joy of liberation.

Photos below

future tense - Closer to Heaven

The painting/cutout is based on a photo from the 1930s when constructing skyscrapers became a strong drive, and the competition to build the world’s tallest building was fierce. I use this image as a symbol of human desire. I replaced the ridiculous-looking hats in the photo with more recent tall buildings, indicating ongoing development and devastation to our environment, using a lone frog to represent nature. The painting is incorporated with a performance by four performers wearing costumes similar to the painting, but with hats made of tree branches or corals. They walk among the crowd, symbolising our hope to reverse the trend and coexist harmoniously with nature.

Ocean Dreaming

A collage of found images explores human agency and our relationship to nature in the painting. Performers wear traffic cone-shaped dresses adorned with coral and fish motifs, suggesting care and an alternative way of relating to the ocean.

about Samba and I

Samba, three old women in Japanese, was formed by three of us who all went University in our 50s and studied Fine Art amongst young UG students. We met through the TESTT studio space in Durham and worked together through group exhibitions focusing on Sustainability and Climate Change. However, we couldn’t realise our first solo exhibition planned in 2019 due to the Pandemic. Last year, for the first time since the Pandemic, we worked together on the Knitted Christmas Tree project and finally, we are putting this small but for us, very significant Samba solo exhibition, Precarious.

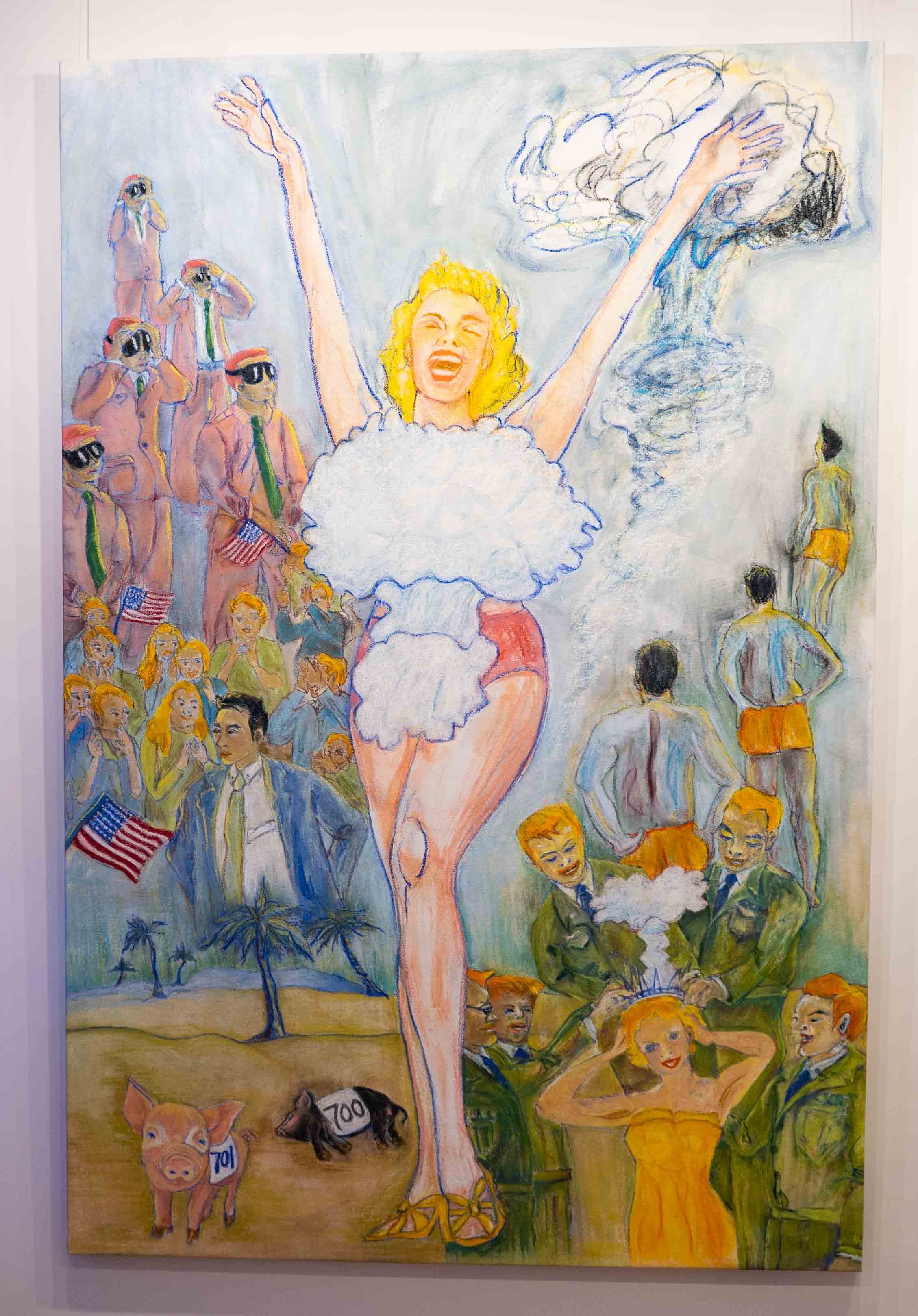

Precarious - Under the Cloud

When I was a young girl in primary school, our teacher brought a thick photo book to class and asked us to pass it around. I can’t even remember exactly what year I was in, but the intense sensation and fear I felt from the images in that book remain vivid decades later. Most of us only managed to look at a couple of pages before passing it along. The page I saw showed a girl about our age, her face blackened and burned, covered in thick, horrible keloids. Her skin and flesh, melted by the intense heat, hung from her bones like a slimy substance, slipping down toward the ground.

It was a brave—and some might say controversial—decision for our teacher to show such shocking images to young children. But I appreciate it deeply. One clever, somewhat cheeky boy in the class proudly announced, “The Americans used the atomic bombs to end the war sooner.” That’s what most of us were made to believe until recently, when formerly strictly confidential U.S. documents revealed another perspective.

Hiroshima is not far from my hometown, and I’ve visited the Atomic Bomb Memorial Park and museums many times. The park is always filled with tens of thousands of paper cranes, folded by people praying for the dead and for world peace. There’s a simple memorial stone overlooking the Atomic Dome, one of the few structures that survived the blast because it was made from steel and stone, unlike the typical Japanese wooden buildings. Inscribed on the stone are the words: “Please rest in peace. We will never make this mistake again.”

My work ‘Under the Cloud’ was triggered by the film Oppenheimer, which received numerous Oscar awards. The movie focuses on J. Robert Oppenheimer, the man who pushed for the creation of the atomic bomb and urged President Truman to drop two different types of bombs on Japan. The film portrays him as a complicated hero. But watching the scene of scientists and officials cheering for Oppenheimer’s success transported me back to my primary school classroom—to that deep fear and sadness I felt as a child. The river that once carried the burned bodies of those who sought water in desperation after the bombing now hosts tourists rowing boats, unaware of its history. Today, even young Japanese people admire the movie’s actor, celebrating him without fully understanding the legacy of his character.

That’s when I knew I had to create this work. I want people to remember and not forget what the Japanese people experienced: the horror of nuclear bombs, and the horror of humanity’s disregard for others.